Giovanni Savino, an Italian photographer based in New York City, worked for CBS News in different capacities for the better part of 20 years. He independently produced a series of documentaries about folkloric music and disappearing oral traditions that were broadcasted on PBS, featured on CNN International and are in the permanent collections of many academic institutions in the United States and abroad. He was a speaker at TED X in Cannes, France where he discussed still photography and film work as a means of cultural preservation. Giovanni is currently a practitioner of Slow Photography, divulging the use of large format equipment and techniques from the past while developing new strategies for the sustainability of analog photography in our digital age. Giovanni manages a tiny large format portraiture studio and darkroom in Manhattan, New York where he continues to offer sittings by appointment and gives analog photography workshops to a small number of students.

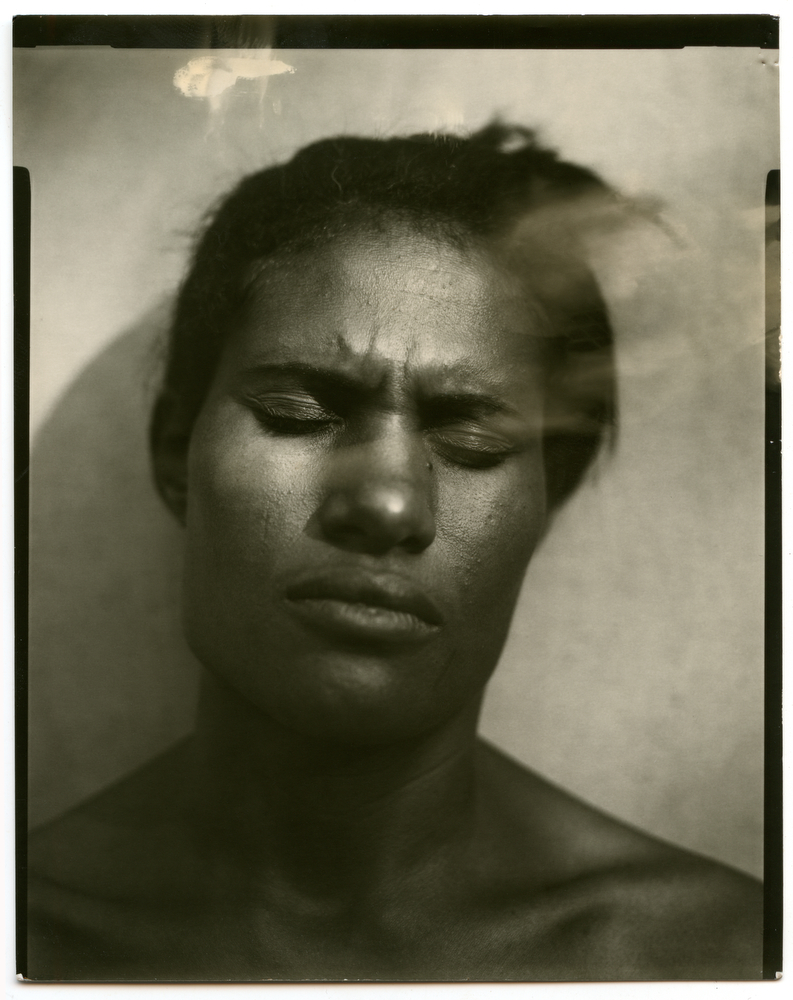

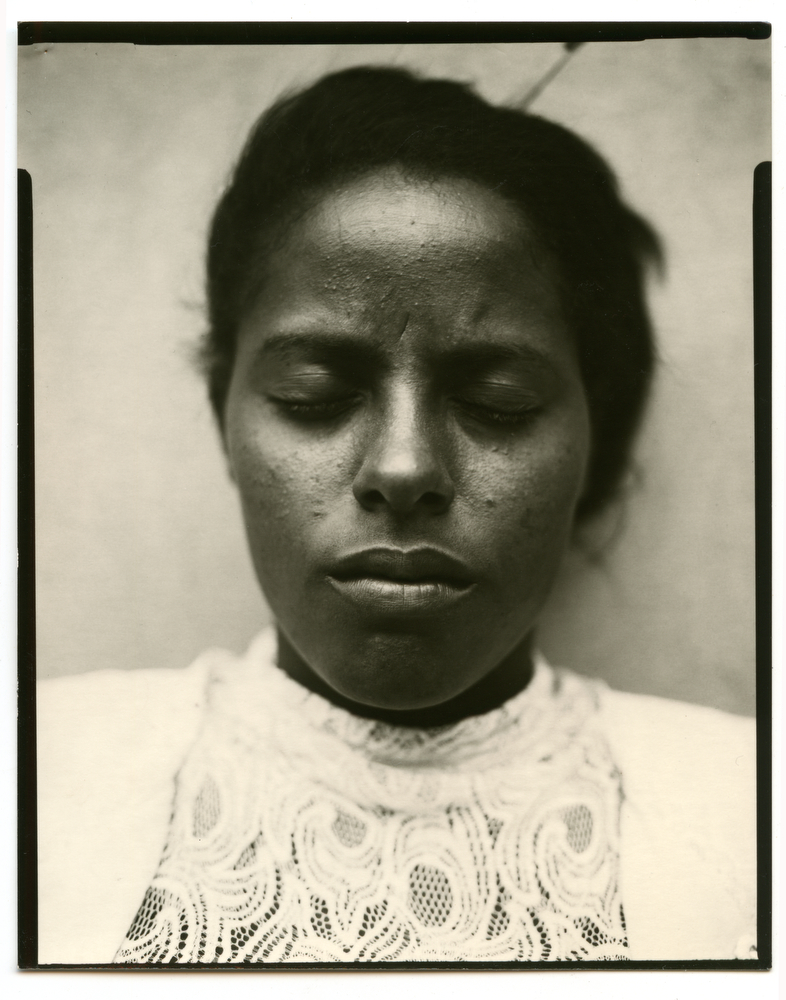

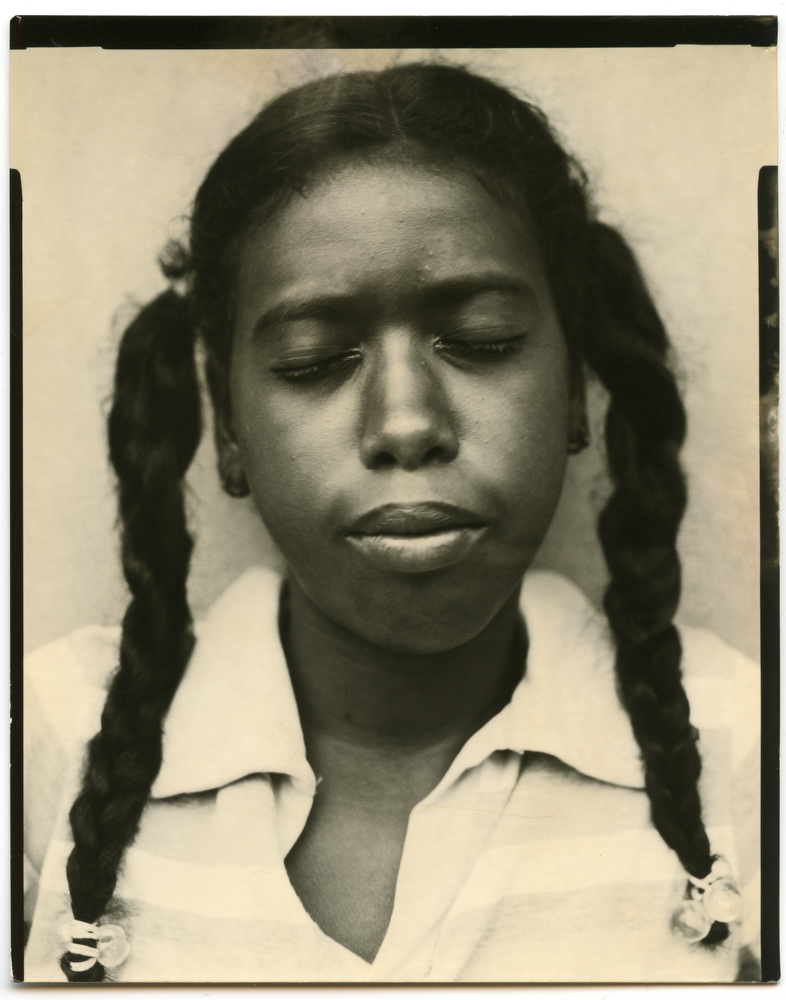

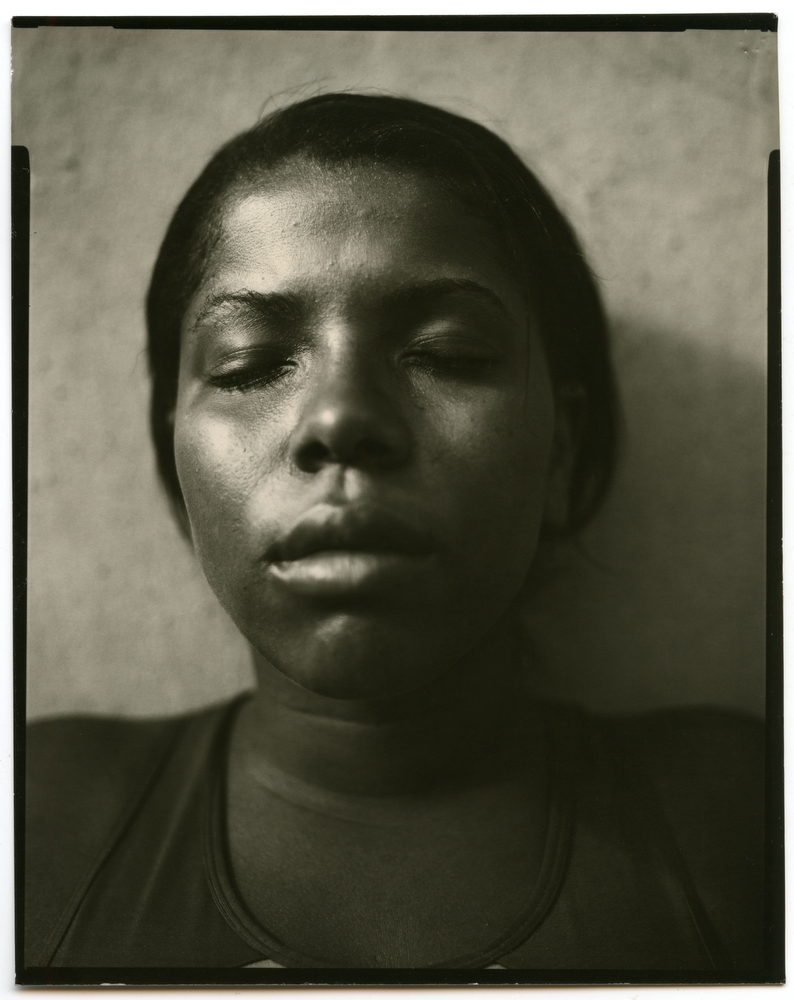

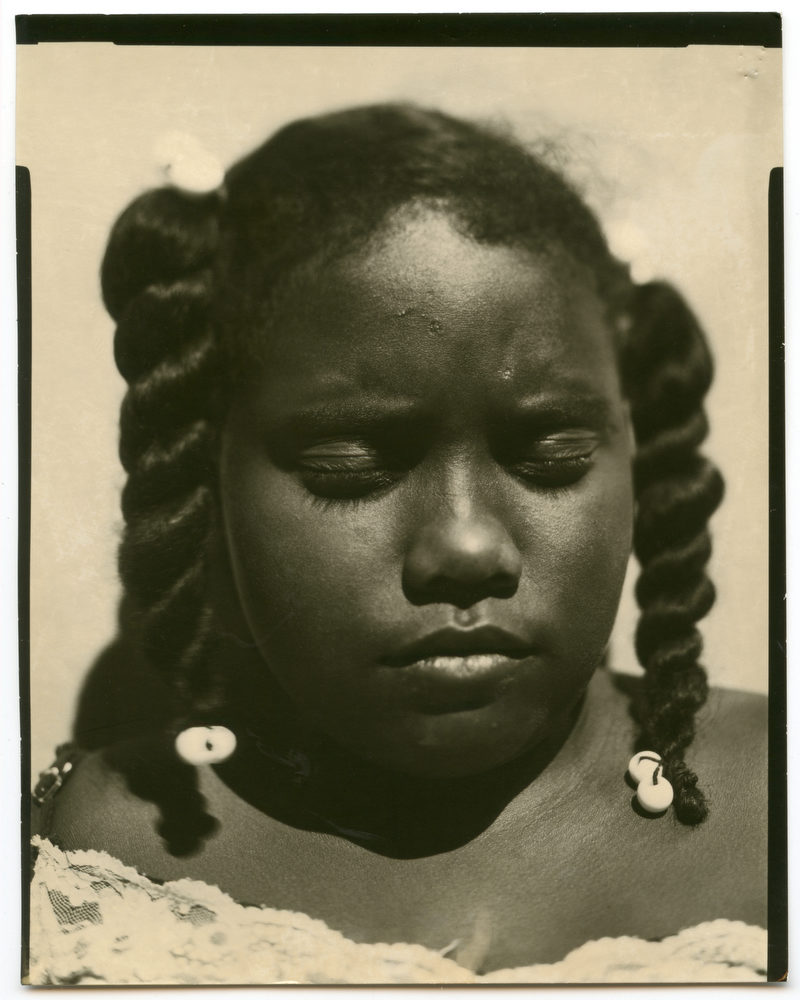

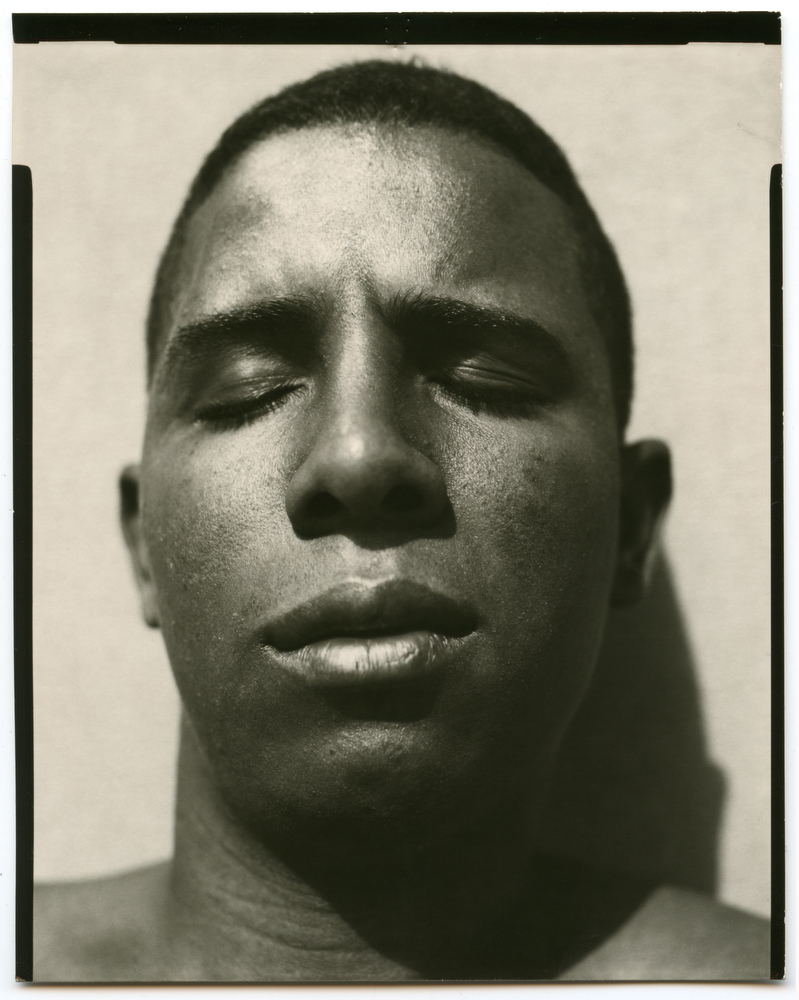

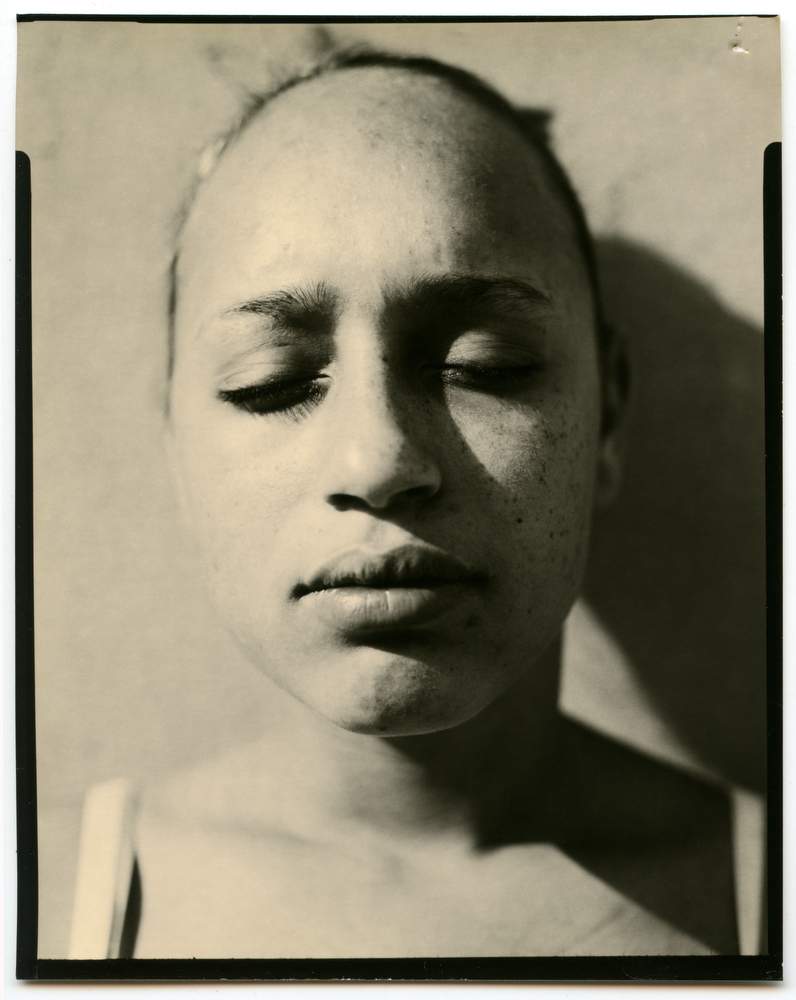

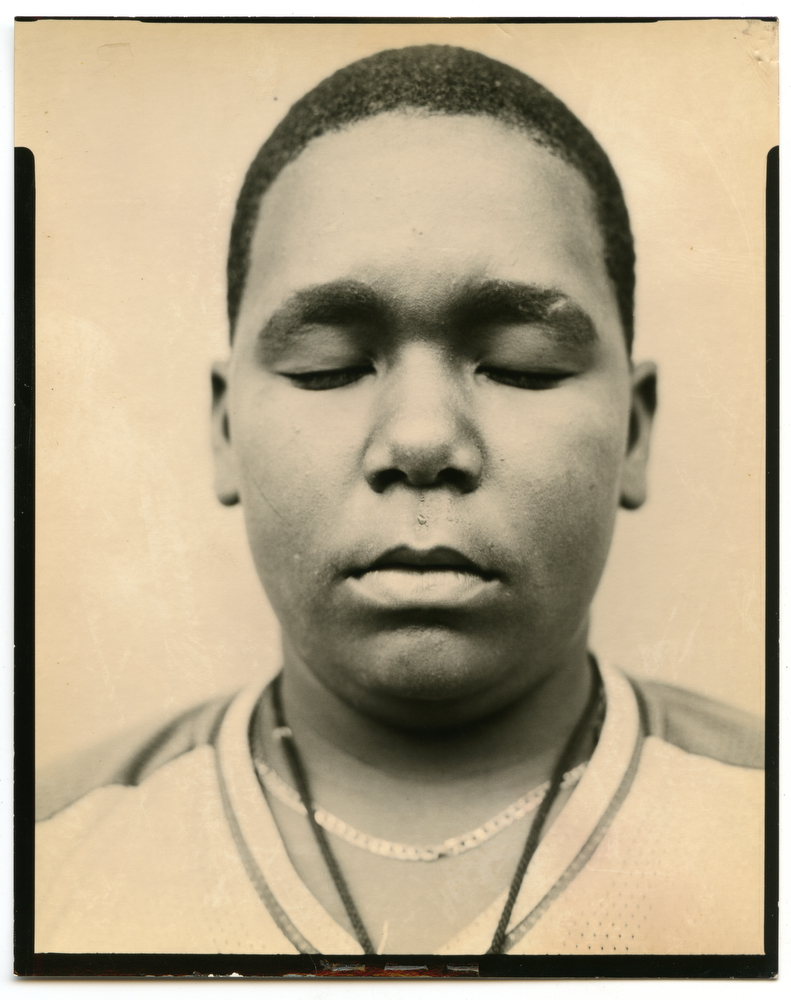

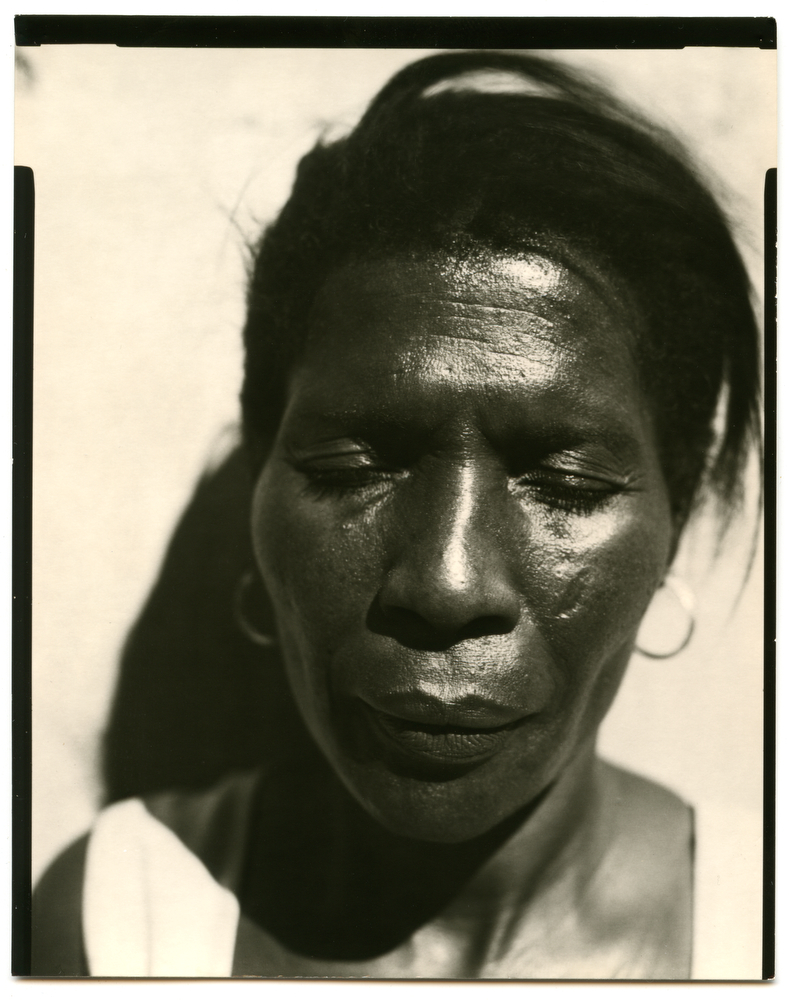

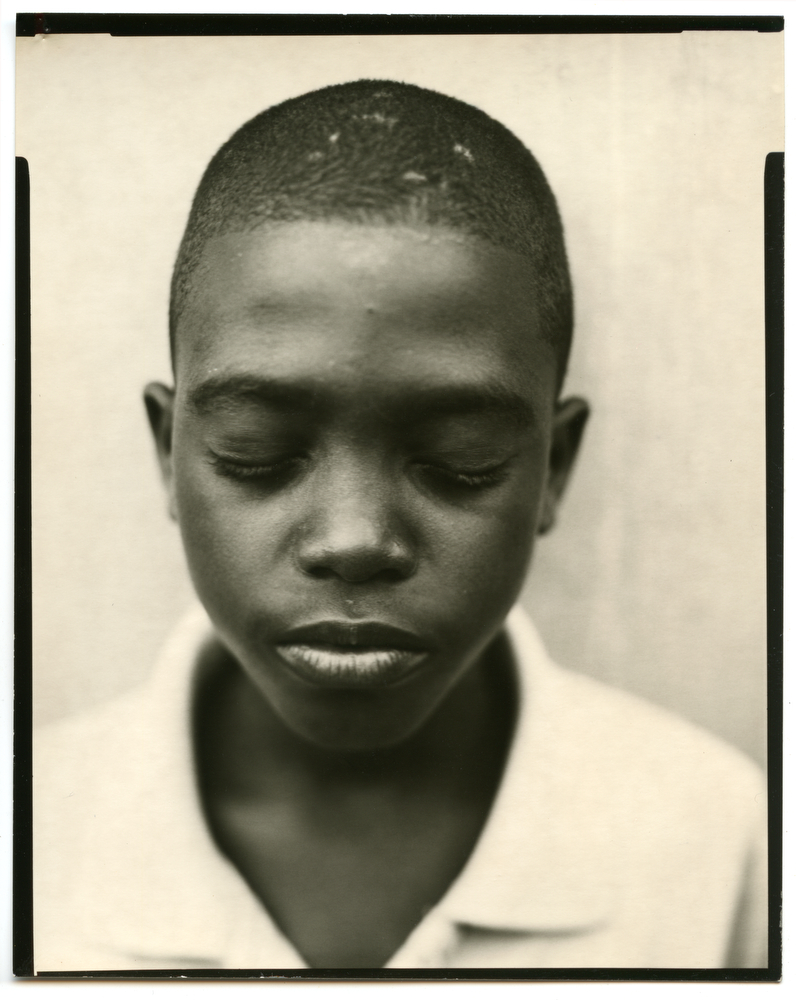

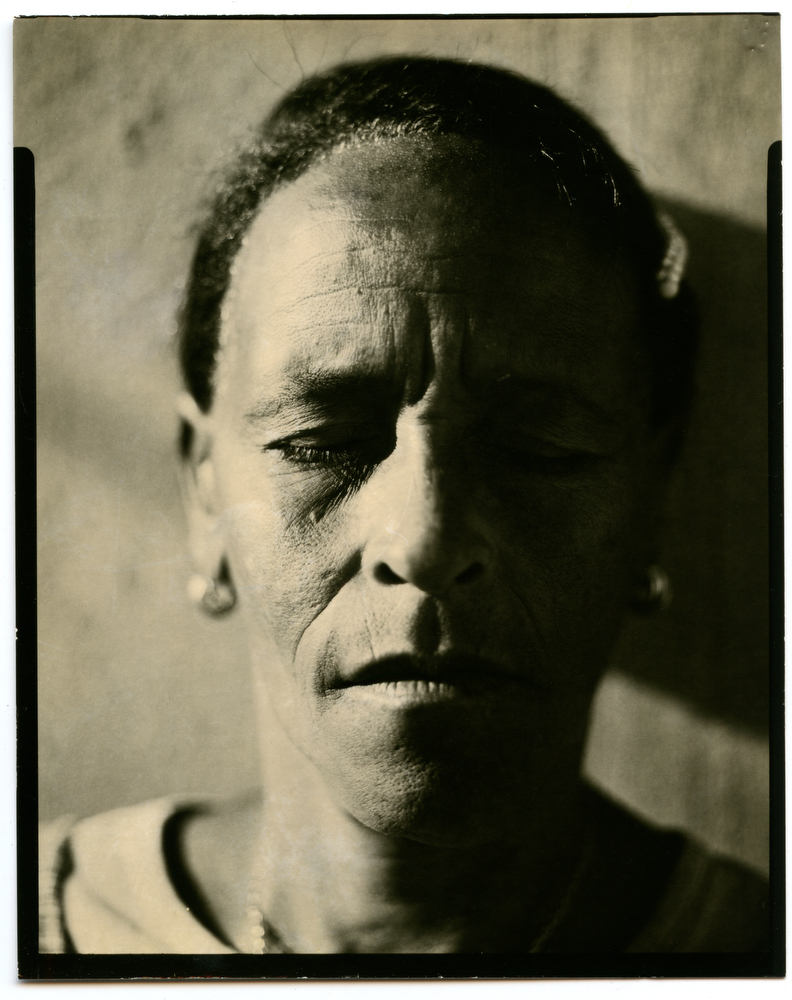

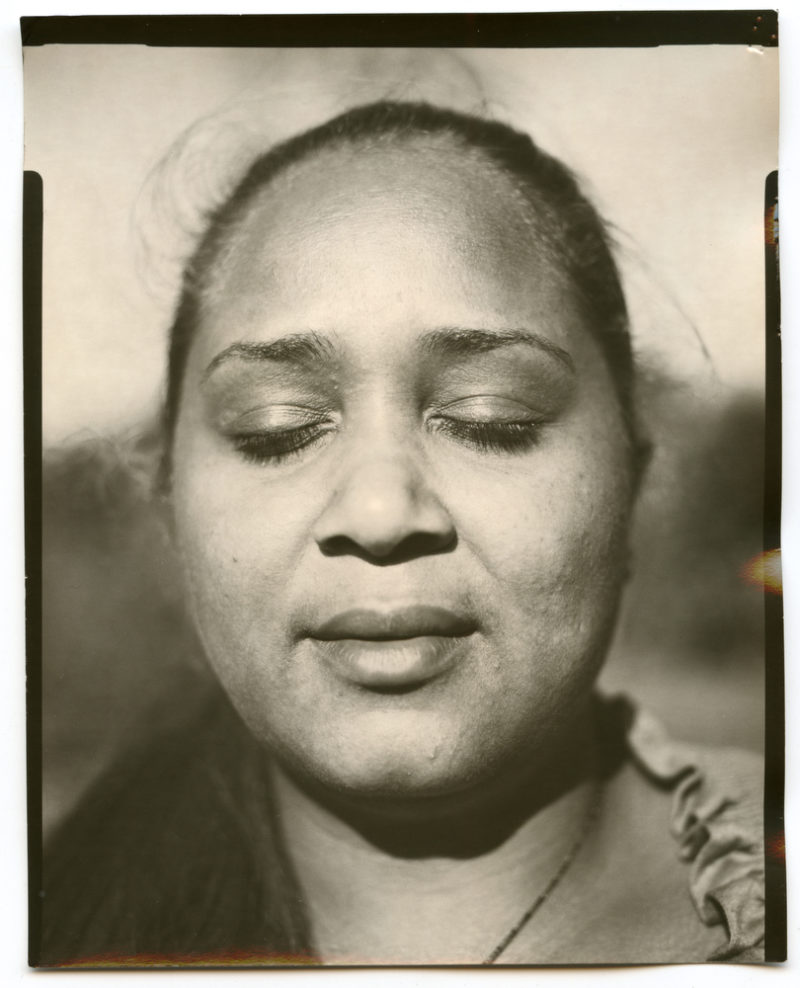

EYES CLOSED

This series of portraits was produced in the Dominican Republic using a 4×5 camera loaded with direct positive paper: each image is unique and it could only be duplicated digitally or by the laborious creation of an inter-negative, by contact, from which to re-print it, trying to match as closely as possible the original image. The choice of working with slow (1 to 3 ASA) positive paper instead of negative film was dictated by the desire to create a series of unique single images–images that would exist on their own, like paintings, and not easily lend themselves to be industrially duplicated. Images that I could hand-develop in the simplest and most organic possible way: by inspection in a rural location using local coffee and washing soda as my developing agent.

Conceptually, I decided to explore an idea that had intrigued me for a long time: portraiture of people with their eyes closed. By coincidence, the only portraits with the subject’s eyes closed that I was ever commissioned to shoot, prior to embarking on this project, were also in the Dominican Republic. On a few occasions I was actually hired to take photos of the recently deceased in their coffins. These were all people who had not owned any other photograph of themselves while they were alive. The post-mortem photos I took of them were used by their family to print the customary “recordatorio”: a small “in memoriam” card with the dead person’s photo, date of birth and death, and a psalm from the bible, usually distributed as a gift among the people attending the funeral and the nine days of grieving. So it wasn’t exactly a casual choice when I decided to shoot this series of portraits of closed eyes in the Dominican Republic.

My work location was a small town near the Haitian border where my wife was born and where I had photographed extensively for the previous fifteen years.

I realized that in portraiture and life alike, our eyes play a most important role in communicating our emotions and socially engaging with others. The eyes are the mirror of the soul: the strongest focal point and emotional indicator while observing a face in our efforts to understand or, at least partially define, the person behind that face. And yet when we close our eyes–the portal to human connections and reality as we know it–a new mysterious universe might open up: the universe of the subconscious, a silent, intimate, yet universally understood language which perhaps can help us open a door onto the antechamber of an afterworld. Photographing someone with closed eyes breaks a long-standing rule in portraiture. Suddenly there is no reciprocal eye connection between the photographed subject and the photographer or the viewer of the final print: there’ s no guessing the subject’s emotions; there is no waiting for a defining stance. The person we look at in the frame could feasibly be asleep, or even dead; removed in a parallel, deeply personal, reality and yet still in front of us. We could say that as viewers of such images we gain a higher level of intimacy. We can unhurriedly observe a person’s facial geography: a privilege usually granted only to close family members or a romantic partner.

On a personal level, another interesting aspect in the making of this body of work was being able to elicit the concentration and human trust necessary for my subjects to fulfill such an “odd request ” from a photographer they didn’t know and sit in front of my lens with their eyes closed long enough for me to obtain a proper exposure. It is worth adding that in over two weeks of shooting I also had to battle innumerable environmental problems. It hadn’t rained in over four months so daily dust storms contaminated all my equipment and a complete lack of running water forced me to fetch it in buckets from a rather distant river in order to develop my photographs at night. Meanwhile, a relentless electrical blackout was effectively isolating me from the rest of the world (no cell-phone/Internet) but luckily also helping me develop my images as the entire town, after sunset, turned into a “natural darkroom”.

To view more of Giovanni’s work please visit his website.