James Hayman is a photographer as well as a film/television director, producer, and cinematographer based in Los Angeles.

After attending The American University for photojournalism, Hayman’s first photography assignment was to photograph Nixon and Brezhnev at the 1973 Washington Summit in the White House Rose Garden. Disenchanted with the paparazzi-like frenzy, Hayman went on to study film at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and post-graduate work at New York University, though his photojournalistic roots still inform his practice today.

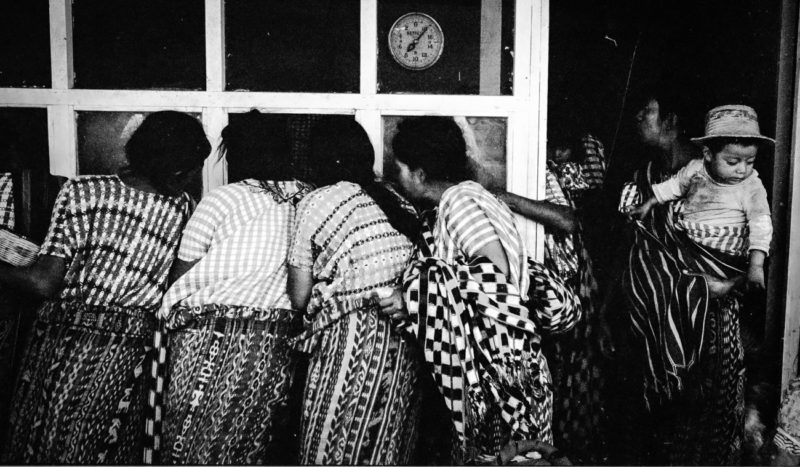

Both his photojournalism and film education led him to travel around the world. He notably traveled to Central America, working for the UN’s disaster relief efforts after the 1976 earthquake in Guatemala. This led to several series of photographic work in the region.

In the 1980s, Hayman began shooting various independent films in New York City, gaining recognition as the cinematographer for An Autumn’s Tale, starring Chow Yun-Fat, which swept the Hong Kong Film Awards in 1987. This led to several years of Hayman working as a cinematographer in China, Japan, and more series of photographic work documenting Asia in the 1980s.

As indie film production in New York City began to end in 1989, he moved to Los Angeles, where he went on to direct and produce multiple television shows and films. Since then, he has directed numerous pilots, including Dangerous Minds and Drop Dead Diva, as well as episodes of The Sopranos, ER, Law & Order, House, Desperate Housewives, and others. Hayman has also worked as an executive producer, most notably on Ugly Betty, which led to winning a Golden Globe Award. He has also been nominated for two Emmy Awards and a Director’s Guild Award.

In addition to his photography archives, Hayman’s current work began in 2014, when he moved to New Orleans to run the television show NCIS: New Orleans. The community, landscape, and culture of the area led him to photograph a series that balances both his eye for humanist cinematography and socio-economic realities.

One of his New Orleans images was accepted into “The Connected World” exhibition at the Los Angeles Center for Photography in May 2020.

Hayman’s recent philanthropic work includes Pack Essentials, providing essential items in New Orleans, and Burnell Grocery’s food program funding in the city’s Lower Ninth Ward. He is also a co-founder of the AllAreOne Fund, which distributes funds around the country to those in need during the pandemic.

Emerald Arguelles: Can you discuss your journey into becoming a photographer, director, producer, and cinematographer?

James Hayman: I guess I was probably about 16 or 17, and an uncle of mine was an amateur photographer. He got me interested in it, and he gave me a camera to use. A friend of the family also did it as a hobby and eventually got sick of it. So he gave me all his old darkroom equipment.

We lived in a rambling old three story home. I took the bathroom in the attic and made it my darkroom. I put a piece of wood across the bathtub and put my trays out, and I had an old Omega enlarger. I just fell in love with it. It clicked for me that I seemed to have an eye to notice framing, style, and humanity. I was curious about all three of those things. So I started shooting.

That took me to college in Washington, DC, at American University as a photojournalism major. At the end of the first year, I got a job working for a news service in DC. My first job was to photograph President Nixon and Soviet President Brezhnev in the White House Rose Garden. I thought I had arrived. It was July in DC, and you had to wear a jacket and tie. I was this crazy hippie and the only jacket I had was this corduroy sport coat. So I wore a corduroy sport coat in July. It’s like 100 degrees, humid, and I’m sweating. I get to the Rose Garden, and it’s like a shark frenzy. There’s like 100 photographers. There’s the front row of guys that sort of have cred, and then there’s the rest of us who are trying to get in and get a frame. I got the shot and I kept working for the news service, but it really soured me to photojournalism.

I really saw myself more from an artist’s point of view. I liked taking my time and finding my images and working with them. Around the same time, I took a film class, and I fell in love with movies. One of the things that drew me to them was that you worked in a group, which was a very different dynamic from working by yourself. At that point, I enjoyed collaboration. So that led me to transfer to the University of California, Santa Barbara, where I finished up my undergraduate in film production. I made a bunch of movies, you know, super 8 and 16 millimeter movies. But I still kept photographing the whole time because those were two sides of my artistic and human personality, being alone and making some art or working with a group and telling a story. I think what that did for my photography was it made it more narrative-based.

When I first started photographing, I always thought that a photographer had to observe and be unnoticed in order to capture a moment without people seeing or reacting to the camera. Now, many, many years later, I interact more with my subjects.

I talk to them, I find out about their lives, I get them to open up or not open up and then I start to photograph them. It’s become a real give-and-take for me that is kind of fascinating. Maybe the years of working as a director and a producer in a narrative world sort of pushed me towards that process. But it was very interesting. Or I find it interesting now.

EA: I love the work that you’ve done in New Orleans. I’m from New Orleans, so to see that was lovely. I haven’t been back in seven years. To see these squares, the people, it brings me back home. How was that experience? And how has that environment, in particular, influenced you but also your later experiences in Central America?

JH: So after undergrad, that’s when I traveled to Central America. I originally went down to put together a portfolio and then use that portfolio to apply to grad school in cinema. So I went to Mexico first, and while I was there Guatemala had a very large devastating earthquake. I was photographing, trying to move through Guatemala, but ended up working for the United Nations down there for quite a while in their disaster relief efforts and photographing what I was seeing. I was there for about nine or ten months.

Then I took a year to put the portfolio together. I lived in Upstate New York on a farm that strangely enough had a dark room. It had been owned by a guy that photographed food and he had built a kitchen that had around 40 fluorescent fixtures in it to light the food. But he also had a dark room. So I put the portfolio together and ended up going to NYU for grad school, where I started getting into movies. I was a cinematographer on indie movies in New York for about 15 years.

One of the first indie movies I did was with friends from Taiwan. We shot the movie in New York’s Chinatown, and it became a big hit. Everyone in New York and the independent film world suddenly thought that I could shoot in the Far East. I’d never been there. I mean, I had shot in Chinatown.

I ended up doing three or four projects in China and Japan over the next couple of years. Then I came back to New York, and there was no more independent film business. I moved to California, got into television, which got me into producing and directing, which got me to a job running a show in New Orleans. So that was six, almost seven years ago, when I moved to New Orleans. The first time I was actually in New Orleans, however, was when I was 16. I was on what they called a domestic exchange where I lived with an African American family in Mid-City and went to their high school for two weeks, and then their son came to New Jersey, where I had grown up.

That was in 1967, around the height of the Civil Rights Movement. It was amazing, and I simply fell in love with New Orleans. To me, it’s a city where either your people are from there or you have run away from something else and gone there.

EA: And then get stuck.

JH: Right? Either you understand the town or you don’t. A lot of people we’d bring from California would be like, everything’s fried here. Yeah and it’s good. It has a special place in my heart, that city. In fact, I still have a house down there.

EA: Oh, that’s amazing.

JH: Yeah. So working in the film business in New Orleans, which is not necessarily a film town, I noticed the town really opened itself up to us and our show. That allowed me to sort of move through different circles I could photograph, areas, particularly socioeconomic areas that maybe I wouldn’t have had such easy access to otherwise. I think that helped me create the body of work that I did in New Orleans, and it really was there that shift from strict observation to narrative interaction really took place.

It reminds me of what someone told me when I first moved there: They said, if you ask somebody how they’re doing, you better have 15 or 20 minutes because they’re going to tell you. When you come in from New York or California it’s like, “What? Don’t answer that.” And now I’ve become that guy. Listen to me now! But I did find that people were very open. There’s a civic and cultural pride in that town that’s like none other. I’m a New Yorker, and there’s a certain pride there, too, but it’s very different.

EA: I lived in the Bronx for four months when I first interned for NBC. I lived in Ohio when I went to high school, but I’ve always been around Southern people and a Southern way of doing things. When I got to New York, there was no speaking. And most you’ll talk to somebody if you’re saying excuse me and that’s about as far as that goes. It’s very interesting to see, even in the boroughs, how certain customs are. In the Bronx, it does seem like more of a Southern type of community in the ways that people are very tight knit. But when I was working in Manhattan, it’s a different world. It’s “don’t talk to me” and “get out of my way.” It was definitely something to get used to because I love the hospitality of the South. That was probably something that was very interesting for you as well.

JH: Yeah, it was. I think it helped me as a person. I grew up in a big Jewish family in New Jersey, and we were always taking in strays, we always had people coming and going, and then I married a woman from Kentucky, who has a big Southern family, and it’s the same way. The people I really connected with in New Orleans were just like that. The crew I put together for the TV show in New Orleans was the most familial crew I’ve ever worked with. We worked hard, we played hard. If people were having a tough time, we took care of each other. I’ve been doing this a long time and in a lot of different places, and I’ve never had that kind of familial attention in a workplace like I found in New Orleans. I think you’re absolutely right, I think it’s a Southern thing. Everyone who moves there either embraces it or moves away.

EA: Is there an intersection between your photography and your directing? I know you touched on the idea of narrative a lot. Is that the intersection or are there other elements to it?

JH: I think as an artist everything you do intersects. It’s all connected somehow. I was a cinematographer for 15 years before I got a shot at directing. That allowed me to hone my sense of composition, framing, and lighting. I tend to enjoy very graphic frames. So that time added to the way I shoot stills. I think actually telling stories as a director, and then as a producer and a showrunner, led to me wanting to tell the stories of my subjects in my photography.

I do acknowledge that I shoot a lot of different stratas of the world, people who are suffering, people who are in need. I do it because I also run a couple of charities, and as hard as it is to look at a photograph like that, which can appear to be exploitative, I think people need to see what’s going on in the world. Maybe it’s my rationalization, but I photograph these subjects because I then try to help these people. If you look at the photographers who really inspire me— Dorothea Lange, Robert Frank, and Danny Lyon—they all were pulling back the veil of what America wants to be and revealing what it is. And that still fascinates me.

EA: To touch on the idea of exploitation: you do help, so I hope there isn’t that feeling of it because it’s something that’s extremely rare. Even in my intro classes, that was a huge thing that people would do, but it would be exploitative because they’d see people down on their luck and they’d use it as an opportunity for what they could gain out of it and not so they could have a conversation and try to connect.

I was reading this book called Art on My Mind by Bell Hooks, and she talks a lot about representation, more specifically of Black Americans. How do we show them? Do we show them down on their luck? Do we show them as royalty? In every way it matters, because there are people who live in each state of that and representing them gives a full grasp of what the community is and what it isn’t as well. So I like that you touched on it because it’s something that a lot of people don’t talk about.

JH: I think that’s a really good point you make about how do you represent people. Because you do want to represent every strata. I have a photograph on my website of a guy under Claiborne Bridge, in front of his tent, and he’s a homeless person. When I asked him if I could take a photo, he immediately saluted. So that is the whole story—bam—right there! That was how he respected himself, so people should see that.

EA: That’s such an interesting dynamic, that pride, because I guess that’s something that people don’t often see. Especially being in the South and in New Orleans, I remember seeing homeless people all the time. I was raised to not cast judgment because you don’t know their story of how they got there. And it’s not always linear, it’s not always that A and B happened, so C happened.

JH: Yeah, and even if you look at the photos I took in Guatemala, it’s the same vibe. You know, people didn’t have much and they still wanted to give to their children, have a job, make a life for themselves. It’s the common denominator, I guess.

EA: So how did your interest in charity and in philanthropy begin?

JH: Well, I grew up in an upper middle class family that always put charity into our world. I think I was taught that if you have then you should give to those that have less. That was part of being a “good” Democrat, and my parents were solid Democrats.

When I went to New Orleans, my assistant and my dear friend Mary Thornton started a nonprofit called Pack Essentials, because there were so many homeless people. She would put together backpacks with socks, water bottles, feminine supplies for women, anything someone needed, and she would pass them out. So I started helping her out financially, photographing one of her distributions so she could put a website together, and then I started helping out in distributing.

Here in Los Angeles during the height of the pandemic, my wife and I and two friends of ours started a charity called All Are One. We basically redistribute stimulus checks to people that couldn’t get them for whatever reason. That’s grown and been taken under the auspices of a larger charity called Following Francis. It’s not just about giving people the money, it’s about giving them a gift, from my heart to yours and to say someone here cares about you. It’s been quite fulfilling.

EA: I think the work that you’ve done in New Orleans is amazing. I remember being in New Orleans and not having a lot. I really didn’t even have a bed. I remember telling my boyfriend I’m a pro at making pallets because I would sleep on the floor so often. Now, being 25 and having an apartment that doesn’t have bars on the windows and has a bed, it’s a different space to be in, and I always try to give back to people. I think to be in that environment to photograph and work in it and still give back is absolutely amazing.

I know the people in New Orleans appreciate that more than you could imagine. We left right before Katrina, it must have been like three or four days before it hit, and we had to pack up everything and move. I remember seeing people who had homes that don’t anymore. The places that they had once lived were now being turned into townhouses and apartments they can’t afford, so they have nowhere to live. That compassion kind of goes away over time, but those people are still there and they still matter. I think for you to see them and to help them is absolutely amazing.

JH: Thank you so much. That’s one thing about our city—because it’s your city, my city— it’s their resilience. Katrina was the capstone of the idea that you will not beat us down, and we will come back. But the Lower Ninth Ward was devastated. The other charitable thing I do involves a friend of mine from Northern California who sent me an article from The Washington Post about a guy in New Orleans. His name was Burnell Colton. He owned a little corner store in the Lower Ninth, and when the pandemic hit, he started giving out food and turned his store into a food bank. So my friend, who sent me the article, asked if I could find him. I said, yeah, I’ll find him. So I went on Google Maps and looked for this market. I clicked on street view, and ended up finding this facade that was in a photo in the article. So I went out there and I introduced myself and I asked how much are you in the hole at this point. He told me, and my friend and I said we were going to make it right. That was no tax write off, no charitable fund. It was simply: you need some money, you’re giving out food, and this is how we’re going to help your neighborhood.

He told me a story of coming back from being in the service right after Katrina and he was the only market in the Lower Ninth. If you wanted to buy food, you had to take a bus to Gentilly or East New Orleans. No one has come into the neighborhood since Katrina to reopen all these corner stores. So I try to help out every time I go there, and I go visit him. I mean, this is a guy who’s just doing it for his neighborhood and his people.

EA: Yeah, I think the Lower Ninth is a spot that’s often forgotten, but it’s the place that got the most damage during Katrina.

JH: Absolutely.

EA: But we stayed out of the Lower Ninth. That’s how I was brought up. You stay out of the Ninth Ward. I grew up in the Seventh Ward, and I lived between there and Chalmette, so I saw all these different pockets of culture. But the Ninth Ward was the place to stay away from. I think that mentality has kind of traveled to other people. So I think for him to even open that up to everyone is absolutely beautiful because that’s something he doesn’t have to do at all.

JH: That’s a really good point that the Lower Ninth has this aura danger about it the same way Harlem has an aura or the South Bronx. And, and it’s not. I mean, yeah, it’s dangerous in the way every place can be, but not to the degree it’s been represented.

EA: You’ve done so much throughout your career. Looking forward, do you have any goals? Not so much even with photography, but in an artistic sense or as yourself?

JH: That’s a good question. I’m lucky that I’ve had some success, so I don’t have to look to my next job. Now I can really pause and see what I want to do, whether I even still want to work in movies or television, or do I just want to work as a photographer or just play guitar, you know.

I do think the charitable work that we’ve embraced over the past year and a half is another thing that I have the opportunity to continue to do and give it more attention. That’s an arena I’d like to keep alive to try to balance my life.

I do have a dream and a couple of ideas of doing a little indie movie.

EA: I love that your journey isn’t linear, and it’s an amazing freedom to have. To choose to give back is even amazing. I’m sorry I keep touching on that, but it’s something amongst artists you really don’t hear too often. Especially in the way that you have. It’s not press coverage. It’s not photographers following you around. These are things you’re doing out of the kindness of your heart, and that’s so rare.

JH: Thank you. I do think artists give back, even if they don’t realize it, in their representation—what you had been talking about a little bit earlier. But I have to tell you, going to a group of people who are homeless, and saying, “I notice you, I care about you, here’s a little bit I can do for you,” it’s one of the most rewarding things I’ve ever done.

EA: You’ll receive those blessings back, I know that for sure.

JH: Yeah, trying to pay it forward.

I will tell you one more New Orleans story. I was shooting my first episode of NCIS: New Orleans, and we were in the French Quarter. It was a huge action sequence, and we were racing the light, the sun was starting to go down—I loved it but it was chaos. In the middle of me saying, “Let’s shoot,” a second line parade comes down Decatur Street. There’s a band, people are yelling, the sound guy is telling me the sound is no good, and I don’t care, I just want to keep shooting.

One by one, I watched my entire crew go over to Decatur Street to dance in the second line. And then I went over and we all danced and had a moment. Then we came back and we finished the scene and life was good. But it was that brilliant realization, that epiphany for me, that if a parade comes by I need to dance. Don’t miss those moments.

To view more of James Hayman’s work, please visit his website.