Carl Martin is an artist and designer based in Athens, Georgia. Trained at the School of Visual Arts in New York, he won a Guggenheim Fellowship for photography and has exhibited in California, New York, Florida and Georgia. His work is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, MOCA GA in Atlanta, the Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in Atlanta and numerous private collections. In 2012 and 2013 recent work of his was published in a four quarterly series called Free Fall by Fall Line Press. In 2018 his book, Carl Martin, was published by Fall Line Press.

Porter: How did you get into photography?

Carl: You know it’s interesting… probably because of my mindset I felt like I could communicate better in photography than I could verbally in a social situation as an awkward kid growing up. I started when I was about 14 when I got my first camera, just started taking pictures of my friends, just super goofy. I was really inspired by the power of snapshots, the power of family pictures, that were structured in such a way to have an impact. Of course, at that time in the late Sixties and early Seventies, Life Magazine was still really big and I was really drawn to photography as a way to communicate. I did notice, even at 14, stuff was happening and time was going by, and photography was a way to experiment and play with that.

Porter: What kind of photography were you looking at growing up?

Carl: Well, to be honest, I was digesting what most of the American popular culture was digesting: artists like Ansel Adams and also a lot of the fashion work that was happening. So that would have been Irving Penn and those classic dudes that were making work. It wasn’t until the Seventies that photography itself became more of a valid art form. So you had a couple Galleries in New York that opened up like the Light Gallery, that started reporting a sort of different way to look at photography or show a different way with what you could do with photography as opposed to just a service to journalism or advertising. So then you had Diane Arbus and those sort of people filter in.

In high school, I worked in the darkroom and was always involved in the annuals and whatever they needed me to do. Nobody taught me, I taught myself. I was a horrible photographer and I still am probably. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing! Nobody bothered to say “try and follow the instructions” or anything. So for most of my time in high school I was feeling my way through and I knew it was what I really wanted to do. I went to college In D.C. for a year and that didn’t really work out. But there was a course at the Corcoran that really saved me. I did a sort of adjunct photography course there and then wound up going to the Maine Photography Workshop which had just initiated a sort of two year certificate program. That was great a year because it was all about the photography. Then I ran my course and moved New York City and attended the School of Visual Arts and got my BA in photography from there. While doing my thesis classes we had these wonderful three-hour-long seminars every week where everyone smoked in the room and filled it up with cigarette smoke and talked about photography and its meaning. And I did that for about two years. I considered graduate school, it was kind of the biggest mistake… well, I don’t know, these days I don’t know what is a mistake and what was not a mistake… but I just needed to make work so I didn’t feel like I needed an institution to do that.

Porter: When you were making work at the Workshop and at SVA were you always doing portraiture or did that come later?

Carl: No, it was always a series of different things. Probably my first serious body of work was in ’79 on the World Trade Center in New York. So I have all these black and white photographs and different scenarios and scenes around the WTC. That was really great and got me to think more about a body of work, refining the process, allowing me to focus. I did that during winter break at the Maine workshop and it got shown around a little bit. I didn’t really start portraiture until this body of work in Athens to tell you the truth. New York is so hard to work in as a field in terms of photographing people you don’t know, it is kind of a different mindset in how it can be utilized. I mean a lot of different photographers have worked in New York and have done amazing work as we know. Many famous street photographers come to mind, and even new ones like Paul Graham. But I couldn’t really get a foothold, so most of my work was more focused on building and bridges, you know, a little more abstract.

Porter: I think most photographers have this notion the people in New York, or really any big metropolitan area, don’t really want to be bothered by a photographer approaching them or asking for a portrait…

Carl: I don’t know if that is true. I mean people are in a rush, for sure, and there is definitely more pressure there. But I think if you look at the guy who did Humans of New York, he found a lot of people to talk to. I think that people are happy for the attention to tell you the truth and I found that out with the portraits I did with this book. People are living all kinds of lives and the contact is interesting and nice. I think that even in New York you can find that.

Porter: Well, I do want to talk about the people in the book. Do you look for something in the people that you choose to photograph? Or is there an element about them that attracts you to them or is it kind of random?

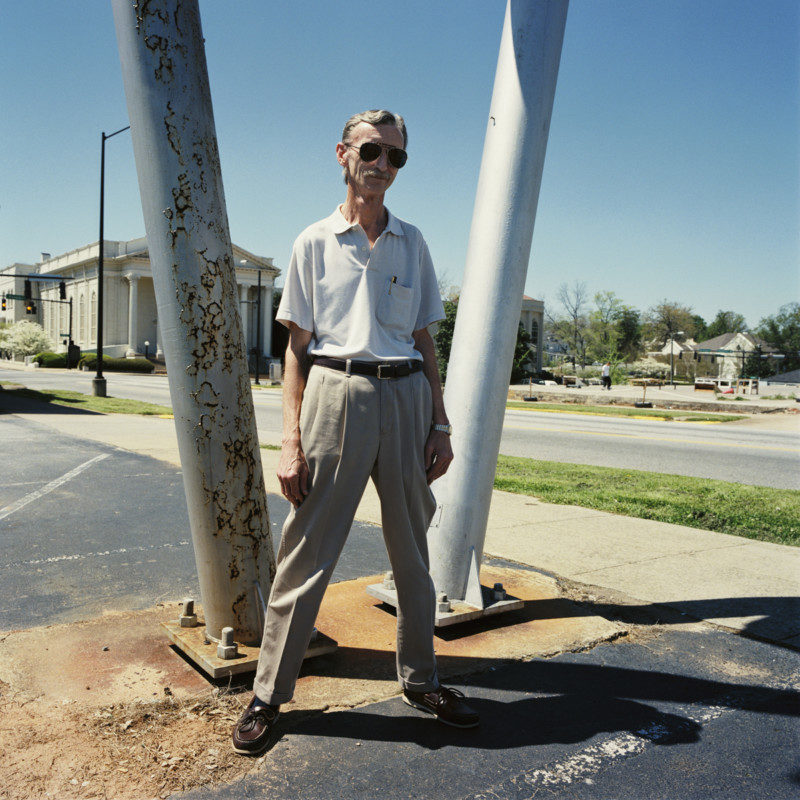

Carl: You are young guy so you might not remember but in the Eighties, while I was cutting my teeth and forging ahead with photography, there was a debate about what had authenticity and what was manufactured and was fake. That debate has largely been settled these days because the world has become much more plastic than it used it to, but in the late Eighties that was a hard edge. Your authenticity was questioned if you worked for “the man” or if you did commercial work or did other things in terms of your artistic credibility. It’s dumb, it’s really just plain out dumb because it really just made things a great deal more difficult than it needed to be. There was a whole consciousness about compromising by not being true to yourself in a way that was authentic. That authenticity for me played out in the people that I photographed (in Athens). I felt like I recognized a level of authenticity of them living their lives and being present of the street, which is where a lot these were made. Outside, in the environment.

The other thing that is really interesting about the people I chose to photograph was that I felt like their story was not being told. I was coming out of New York City, which is to say I was coming out of a bubble, a particular bubble. So when I moved back South I was a little taken aback to see the progress that I felt like had been made in the 10 years prior was not a part of the visual evidence in our culture. The severe poverty, the interracial divide, all the social ills that still permeate our conversation today. That was all there so what I really wanted to do was create a platform for these people to be seen, and so that permeated into how the photographs were structured so that (the photographs) would have a visual interest and then maybe, years down the line, someone can see the photograph and see the subject in years to come.

Porter: A lot of work, if not all of the work in this book was made in-and-around Athens, and there other people who make a lot of work in the same area…

Carl: There are a lot of others… I think you are trying to say, Mark Steinmetz…

Porter: Yeah, Mark definitely comes to mind, but the way you photograph is different than them. I guess what I am trying to get at is that when I look through your work or your book I’m not sure I see the Athens I thought I grew up in. Which is funny to me because I know all the corners where they were being taken, but the people in them don’t speak to this town in singularly, they speak more to the broader Deep South.

Carl: To be honest, I don’t think that we can claim a particular regionality, I think what’s in my book is everywhere.

Porter: Right, you can take a step back and see the South, and it definitely looks like the South, but if you take an even further step back and make the argument this is all over America. The people are laborers who have that working to survive mentality.

Carl: I felt like it permeates everywhere and it needed to be seen. All the work in the book was made in the ’90s and I don’t think that the issues of poverty or social divides were in the topic of discussion like they are today.

Porter: Do you feel like you could photograph anybody?

Carl: That’s a very good question. I don’t want to photograph just because there is a particular anomaly, or there is a weirdness… I’m not looking for leverage in what I photograph. I mean I have shifted, for sure, in what I was interested in photographing in the ’90s to the 2000s and the people in them are really different. So, can I photograph anybody? I mean, would I choose to photograph anybody? Definitely not, because there are people that I am just not interested in, who don’t question my sense of reality in ways that I find them interesting. So I guess the answer would be no… but I’d be happy to look.

Porter: Your book is kind of a catalog of all of your work in that its a few projects sequenced together into one. I don’t know if you feel this way, but they really work well together, with a major trope of the book being the automobile and salvage yards. I am curious what drew you to those places.

Carl: In October of ’89, there was a big stock market drop and a rescission in the country. We moved here in 1990, so I started work then and I just kept seeing culture, with a racial division, that I felt like that really stuck in a lot of different ways. If you look closely at the poor African American population and the poor white population it is identical in many ways to really divide the lower classes from the upper and middle classes in order to keep control. So what I saw was a culture that was really stuck and the automobile, which is ubiquitous in American culture and the center of culture. Our culture is designed around the success of the automobile and the transportation of ourselves through automobiles. The kind of thinking I came upon was that everybody has got wheels but nobody going anywhere. So I was looking at this idea of mobility as a kind of anti-metaphor as the sort of lack of mobility that we see in our culture. I was working with a lot of these people in the (construction) business.

Porter: Can you talk a little bit about working with Fall Line Press?

Carl: Fall Line is… you know, how many people do you know what is doing that? There is just not that many people. Bill Bolling, the publisher and I have been talking about doing this book for about four or five years now. Bill is just such a great guy; very enthusiastic; loves photo books; he is a photographer himself and besides him, none of us had really done a book before. Michael David Murphy was the editor of the book and I gave him stacks of 5×7 prints and he worked his way through it. There were some banter and a fair bit of collaboration but really Michael drove the editing process. Bill’s daughter, Meghan Fowler, designed it. And obviously we there are always one or two things that you wish you could go back and change, but it’s out there and that what is important.

To view more of Carl Martin’s work please visit his website.