Evan Allan is a Brooklyn based photographer working primarily with the constructed American landscape. He grew up in the mountains of Western North Carolina and received his BA from UNC Chapel Hill in 2014. His work has been featured in various print and web publications and he was shortlisted for the Palm* Photo Prize in 2019. In 2020 he was selected to attend the Chico Hot Springs Portfolio Review with his book series “The Tiger Beetle”.

The Tiger Beetle

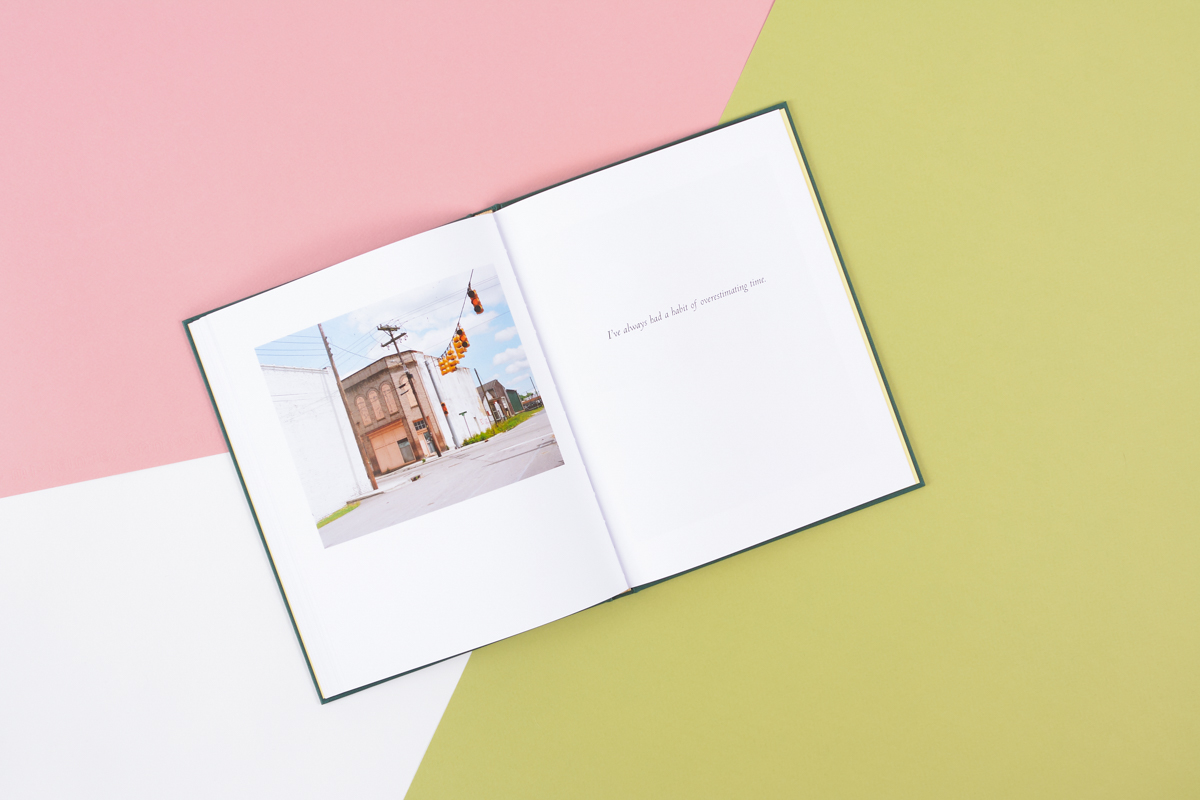

The Tiger Beetle is a fragmented travelogue created during a month-long road trip across the United States. Within, photographs of roadside relics and found language reveal an American landscape of contradiction, equal parts humor and sorrow. Accompanying these images are context-less snippets of thought, memory, and conversation in the form of original text. Together these travel photographs and short non-sequiturs describe a countryside full of mysterious symbols and double meanings.

Though primarily a meditation on travel photography, themes of memory, home, and the ambiguity of language also slip in between the pages.

Kyra Schmidt: Can you start by telling us a little bit about how your series The Tiger Beetle came to be? What was your initial intention when you set out on your month-long road trip?

Evan Allan: For sure! I’d been interested in the idea of the photographic road trip for some time. It’s something that’s indefinitely baked into the history of the medium, especially in America, and some of my favorite photographers like Joel Sternfeld, Stephen Shore and more recently Alec Soth and Jason Fulford have established careers based on working on the road. So I was definitely looking for an excuse to try making a travel project.

Back in late 2018, I applied to a portfolio review located in Montana. I decided that if I got in I would take a month off and make work along the way. When I was ultimately rejected I decided to go on the trip anyway. Going into it I was hoping the body of work would end up becoming a book. I had made a few self-published zines in the past, so I knew print was where I wanted any serious projects to end up. That being said, I didn’t want to disappoint myself if the work didn’t come together in an interesting way. The way I shoot and find subjects I’m often at the mercy of chance. As I photographed on the road, I tried to stay very open to whatever I happened to find – still, a book was always in the back of my mind.

Kyra Schmidt: I personally am mesmerized by the text in the book. Especially as it is intertwined with single and double-page spreads, and blank pages that form their own rhythmic beat. Your statement includes that they are “context-less snippets of thought, memory, and conversation in the form of original text.” Can you offer us any more insight into how you chose the stream-of-conscious language, or how you decided to sequence it for book form?

Evan Allan: The first few drafts of the book didn’t have any text at all. I was showing a friend the work and they asked if I’d considered adding a text component. It did feel like something was missing and text was something I’d thought about, but I always imagined it would be more of a collaborative thing. My brother is a poet, so I thought having him write a response to the images might be interesting, but I realized pretty quickly that I had a specific voice in mind and it didn’t feel right trying to push his work towards something that wasn’t natural. Instead, I decided to try writing something myself. I took a week and started writing out the most potent memories from the trip. Some of them were obviously notable at the time, like a semi-truck demolishing a deer in front of me, while other things – like the history of the Madison, Wisconsin capitol building – only revealed itself as important after a fair amount of introspection.

I took those blocks of text and tried to pare them back to their absolute essentials. I wanted text in the book to function similarly to a photograph, so it had to describe and suggest meaning but also leave a lot of room for interpretation. I think that like photos, text has a natural ambiguity that you can play with, photos always lack a greater context and text can lack tone. It’s a bit of a tightrope walk though because you don’t want the work to be too ambiguous to be accessible.

I’m really glad you mentioned the text being like a drumbeat because that’s exactly how I always hear it in my head. The text gave my sequencing a steady rhythm that the photographs could compliment and riff off of. I see the book as being composed of a few distinct “movements” where the text and images combine to create a rise and fall of tension. A lot of photos in the book contain text themselves, so it was important for me to give everything its proper breathing room, that’s why you often have text on a spread by itself instead of next to a photograph. Really I almost always like to keep text and images separate, when they’re next to each other I worry about their connections being too heavy handed. In terms of the sequencing itself, for me it’s a really intuitive process that involves a lot of mulling and then sudden action.

Kyra Schmidt: It’s funny, it seems as if most creative actions evolve out of a sudden and spontaneous gut feeling. While we are on the topic of text, what is the significance of the tiger beetle and how did it come to grace the title of the book?

Evan Allan: It’s certainly always the case with me! I think a big way to improve as an artist is to learn how to shape your environment to properly utilize those moments of inspiration. For me it’s always having prints of work in-progress spread out on my bedroom floor.

The Tiger Beetle title came about pretty late in the process. When I was writing the text, I was thinking about a day I spent in the Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge, which is right outside Denver. I was walking along a sandy path and every few steps an array of insects would flee a few feet ahead. I don’t think they were tiger beetles but the way they moved reminded me of trying to catch them when I was a kid. The tiger beetles in North Carolina are this beautiful iridescent green-blue, so they were quite captivating but I’d totally forgotten about them until that moment.

I started researching tiger beetles and read that when they’re hunting they move so fast they render themselves blind. The connections between that fact and my thoughts on travel photography felt too perfect to ignore, so I added it in as a piece of text. That text working in combination with a few images quickly became one of the most important sections of the book. It really helped tie together the major ideas I was exploring, travel photography, memory and language.

My original title for the book was “Month of May” since the trip took place primarily in May and it’s also my birth month. I was showing the work to a friend and referencing the text, he mentioned that he thought “The Tiger Beetle” would make a better title. I’d actually written “Chasing the Tiger Beetle” down in my list of potential titles while on my trip, but I think getting that outside confirmation really helped convince me to change it. It leans more to the personal side of the work, but in hindsight I’m really glad that it’s called The Tiger Beetle.

Kyra Schmidt: I feel like making a book is now an integral part of being a photographer today, but I also think this opens up a lot of room for creativity in new ways. In photographing this series, then sequencing the book, were there some challenges you couldn’t have foreseen?

Evan Allan: Making a book does seem to almost be a rite of passage for certain circles of photography. I agree, the physicality of a book gives you a lot of room to play and creatively elevate the work inside. Speaking of which, something I couldn’t have foreseen was that my first cover material choice was deemed too thin when we sent the book to press. We had to scramble a bit, but I’m happy we were able to use a buckram in the same color as my original selection.

The most unexpected challenge was the physical and mental toll of being out on the road for a month. I say a month but really I stopped wanting to take pictures after about three weeks. In addition to the many miles of walking a day, figuring out where I was going to sleep that night, etc. keeping my eye “on” and aware of the world for such an extended period of time totally exhausted me. It was really interesting, and a bit scary, to suddenly discover my limits.

Kyra Schmidt: I can only imagine. Do you have a favorite image within the book? Or perhaps one that represents a significant moment from this journey?

Evan Allan: I’d have to say my favorite image is the one of the butterfly trapped in glass. Most of the photos in my book aren’t monolithic. They need the other images and the text to prop them up but that doesn’t feel like the case with the butterfly photo. When I’m sequencing, in addition to formal connections, I’m also thinking about what the images symbolically represent and how I can use that to stitch together meaning. For me, a photo usually represents an idea, a word or a feeling and the meaning builds as the sequence progresses. If each photo is usually a word, the butterfly image feels like a sentence by itself. I’m drawn to subjects that feel like contradictions – the butterfly is beautifully vibrant but you also know it’s dead. Its cage is glass but the edges are sharp and visible. It feels like a reflection on the medium thinking of “capturing” and “framing” subjects. There’s an interview I love with the photographer Gus Powell where he stresses his desire for his photobooks to be read rather than people seeing the images as “a bunch of butterflies trapped in a display case.” So maybe I had that in the back of my mind as well.

Making that photo felt like something of a breakthrough. I took it in my Butte, Montana AirBnB a few days after I lost my desire to photograph. It’d been raining and unseasonably cold so I’d been cooped up inside reflecting on the whole trip. Getting those few rays of sun and being able to make this image gave me hope.

Kyra Schmidt: The Tiger Beetle Is your first published monograph. Congrats by the way! Where do you see your work moving from here?

Evan Allan: Thank you! I think I’d been putting a lot of pressure on myself to publish my first book. Now that I have I feel like I can relax a bit more and really take my time crafting my next project. I’ve been taking photos in my home state of North Carolina for a few years and I feel like that’s where I want to base my next series. After making a project on the road I’m eager to spend some time in familiar surroundings. I have a few ideas knocking around my head, something about Southern identity. But I’m trying to take it slow, I have a history of getting ahead of myself.

Kyra Schmidt: Thanks so much for this wonderful conversation, Evan! To leave us off, who or what are some of the biggest influences on your work? Is there a particular artist, book, or image (aside from your own) that resonates with you?

Evan Allan: Thank you for all the interesting questions Kyra! This was a lot of fun.

I’d say the biggest influence on The Tiger Beetle has to be the work of Jason Fulford. The way his books, The Mushroom Collector and Hotel Oracle, combine text and image had a huge impact on me. I also really admire how playful he is as an artist. Every new book he makes feels like an experiment in sequencing and design but the work is always distinctly his.

To view more of Evan Allan’s work please visit his website.

To order a copy of The Tiger Beetle, visit the shop today!